For 70 years, China and the United States have managed to avoid disaster over Taiwan. But a consensus is forming in U.S. policy circles that this peace may not last much longer. Many analysts and policymakers now argue that the United States must use all its military power to prepare for war with China in the Taiwan Strait. In October 2022, Mike Gilday, the head of the U.S. Navy, warned that China might be preparing to invade Taiwan before 2024. Members of Congress, including Democratic Representative Seth Moulton and Republican Representative Mike Gallagher, have echoed Gilday’s sentiment.

There are sound rationales for the United States to focus on defending Taiwan. The U.S. military is bound by the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act to maintain the capacity to resist the use of force or coercion against Taiwan. Washington also has strong strategic, economic, and moral reasons to stand firm on behalf of the island. As a leading democracy in the heart of Asia, Taiwan sits at the core of global value chains. Its security is a fundamental interest for the United States.

Ultimately, however, Washington faces a strategic problem with a defense component, not a military problem with a military solution. The more the United States narrows its focus to military fixes, the greater the risk to its own interests, as well as to those of its allies and Taiwan itself. War games held in the Pentagon and in Washington think tanks, meanwhile, risk diverting focus from the sharpest near-term threats and challenges that Beijing presents.

The sole metric on which U.S. policy should be judged is whether it helps preserve peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait—not whether it solves the question of Taiwan once and for all or keeps Taiwan permanently in the United States’ camp. Once viewed this way, the real aim becomes clear: to convince leaders in Beijing and Taipei that time is on their side, forestalling conflict. Everything the United States does should be geared toward that goal.

To preserve peace, the United States must understand what drives China’s anxiety, ensure that Chinese President Xi Jinping is not backed into a corner, and convince Beijing that unification belongs to a distant future. It must also develop a more nuanced understanding of Beijing’s current calculus, one that moves beyond the simplistic and inaccurate speculation that Xi is accelerating plans to invade Taiwan. Support for Taiwan should bolster not only the island’s security but also its resilience and prosperity. Assisting Taiwan will also require new U.S. investments in tools that benefit the island beyond the military realm, including a more holistic deterrence strategy to deal with Beijing’s coercive gray-zone tactics. Critics may contend that this approach sidesteps the hard questions at the root of the confrontation, but that is precisely the point: sometimes, the best policy is to avoid bringing intractable challenges to a head and kick the can down the road instead.

SEA CHANGE

In the final years of the 1945–49 Chinese Civil War, the losing Nationalists retreated to Taiwan, establishing a mutual defense treaty with the United States in 1954. In 1979, however, Washington severed those ties so it could normalize relations with Beijing. Since then, the United States has worked to keep the peace in the Taiwan Strait by blocking the two actions that could lead to outright conflict: a declaration of independence by Taipei and forced unification by Beijing. At times, the United States has reined in Taiwan when it feared the island was tacking too close to independence. In 2003, President George W. Bush stood next to Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao and publicly opposed “comments and actions” proposed by Taipei that the United States saw as destabilizing. At other times, the United States has flexed its military muscle in front of Beijing, as it did during the 1995–96 Taiwan Strait crisis, when U.S. President Bill Clinton sent an aircraft carrier to the waters off Taiwan in response to a series of Chinese missile tests.

Also important to the U.S. approach have been statements of reassurance. To Taiwan, the United States has made a formal commitment under the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act to “preserve and promote extensive, close, and friendly commercial, cultural, and other relations” with Taiwan and to provide the island “arms of a defensive character.” To Beijing, the United States has consistently stated that it does not support Taiwan’s independence, including in its 2022 National Security Strategy. The goal was to create space for Beijing and Taipei to either indefinitely postpone conflict or reach some sort of political resolution.

For decades, this approach worked well, thanks to three factors. First, the United States maintained a big lead over China when it came to military power, which discouraged Beijing from using conventional force to substantially alter cross-strait relations. Second, China was focused primarily on its own economic development and integration into the global economy, allowing the Taiwan issue to stay on the back burner. Third, the United States dexterously dealt with challenges to cross-strait stability, whether they originated in Taipei or Beijing, thereby tamping down any embers that could ignite a conflict.

Over at least the past decade, however, all three of these factors have evolved dramatically. Perhaps the most obvious change is that China’s military has vastly expanded its capabilities, owing to decades of rising investments and reforms. In 1995, as the United States sailed the USS Nimitz toward the Taiwan Strait, all the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) could do was watch in indignation. Since then, the power differential between the two militaries has narrowed significantly, especially in the waters off China’s shoreline. Beijing can now easily strike targets in the waters and airspace around Taiwan, hit U.S. aircraft carriers operating in the region, hobble American assets in space, and threaten U.S. military bases in the western Pacific, including those in Guam and Japan. Because the PLA has little real-world combat experience, its precise effectiveness remains to be seen. Even so, its impressive force-projection capabilities have already given Beijing confidence that in the event of conflict, it could seriously damage the United States’ and Taiwan’s forces operating around Taiwan.

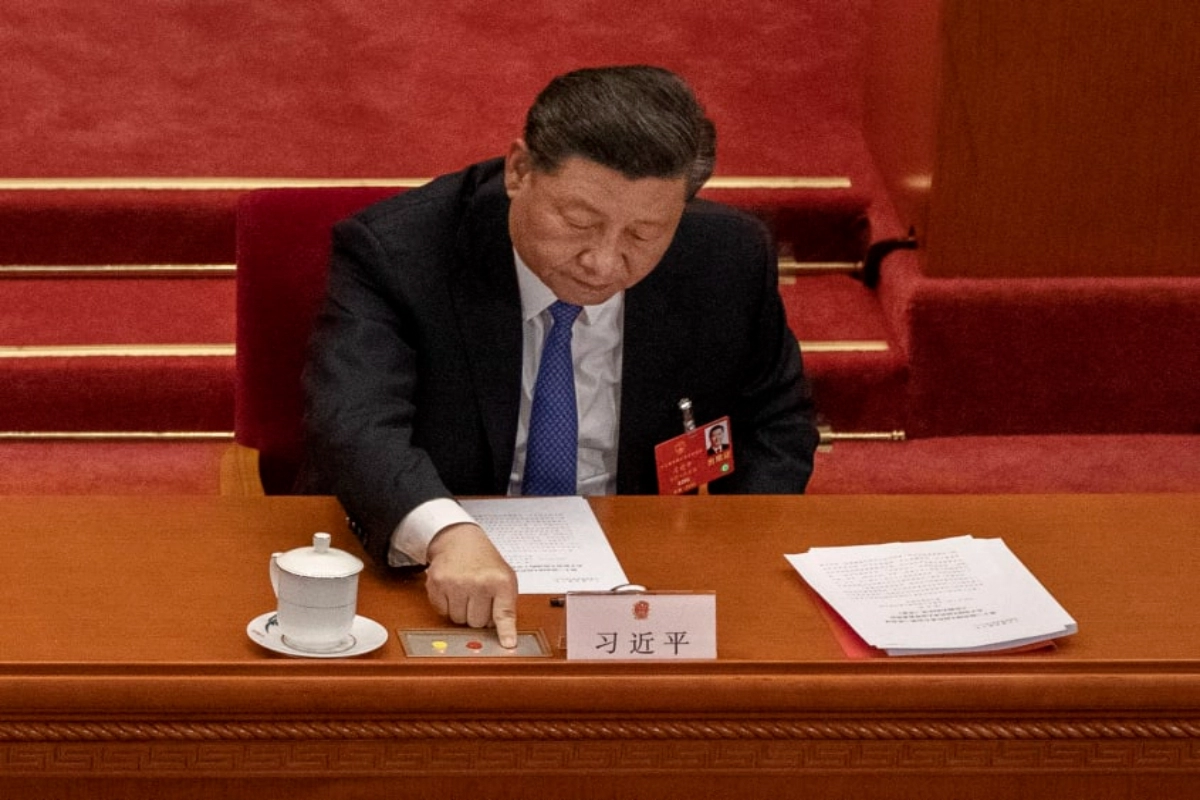

Alongside China’s military upgrades, Beijing is now more willing than ever to tangle with the United States and others in pursuit of its broader ambitions. Xi himself has accumulated greater power than his recent predecessors, and he appears to be more risk-tolerant when it comes to Taiwan.

Finally, the United States has abandoned any pretense of acting as a principled arbiter committed to preserving the status quo and allowing the two sides to come to their own peaceful settlement. The United States’ focus has shifted to countering the threat China poses to Taiwan. Reflecting this shift, U.S. President Joe Biden has repeatedly said that the United States would intervene militarily on behalf of Taiwan in a cross-strait conflict.

READY, SET, INVADE?

Driving this change in U.S. policy is a growing chorus arguing that Xi has decided to launch an invasion or enforce a blockade of Taiwan in the near future. In 2021, Admiral Philip Davidson, then the head of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, predicted that Beijing might move against Taiwan “in the next six years.” That same year, the political scientist Oriana Skylar Mastro likewise contended, in Foreign Affairs, that “there have been disturbing signals that Beijing is reconsidering its peaceful approach and contemplating armed unification.” In August 2022, former U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Elbridge Colby wrote, also in Foreign Affairs, that the United States must prepare for an imminent war over Taiwan. All these analyses base their judgments on China’s expanding military capabilities. But they fail to grapple with the reasons why China has not used force against Taiwan, given that it already outmatches the island in military strength.

For its part, Beijing has stuck to the message that cross-strait relations are moving in the right direction. China’s leaders continue to tell their people that time is on their side and that the balance of power is increasingly tilting toward Beijing. In his speech at the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Beijing in October 2022, Xi declared that “peaceful reunification” remains the “best way to realize reunification across the Taiwan Strait,” and that Beijing has “maintained the initiative and the ability to steer in cross-strait relations.”

Yet at the same time, Beijing believes that the United States has all but abandoned its “one China” policy, in which Washington acknowledges China’s position that there is one China and Taiwan is a part of it. Instead, in the eyes of Beijing, the United States has begun using Taiwan as a tool to weaken and divide China. Taiwan’s internal political trends have amplified China’s anxieties. The historically pro-Beijing Kuomintang Party has been marginalized, while the independence-leaning Democratic Progressive Party has consolidated power. Meanwhile, public opinion in Taiwan has soured on Beijing’s preferred formula for political reconciliation, the “one country, two systems” policy, in which China rules over Taiwan but allows Taipei some room to govern itself economically and administratively. Taiwan’s public became especially skeptical of the idea beginning in 2020, when Beijing abrogated its promise to provide Hong Kong a “high degree of autonomy” until 2047 by imposing a hard-line national security law. In high-level pronouncements, Beijing has reiterated that “time and momentum” are on its side. But beneath public projections of confidence, China’s leaders likely understand that their “one country, two systems” formula has no purchase in Taiwan and that public opinion trends on the island run against their vision of greater cross-strait integration.

Also Read: Congress demands resignation from Fadnavis

Taipei has its own sense of urgency, driven by concerns over Beijing’s growing military might and the ongoing worry that U.S. support might diminish if Washington’s attention shifts elsewhere or Americans turn against overseas commitments. The new refrain from the administration of Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen—“Ukraine today, Taiwan tomorrow”—is both a genuine reflection of Taipei’s worries about Chinese aggression and an attempt to galvanize support that will extend beyond the current geopolitical upheaval. In other words, the one thing that Beijing, Taipei, and Washington seem to agree on is that time is working against them.

Any approach to maintaining peace in the Taiwan Strait must begin with understanding how deeply political the issue of Taiwan is for China. It is noteworthy that the 1995–96 Taiwan Strait crisis and the recent spike in tensions over Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan were driven by issues of high political visibility—not by U.S. arms sales to Taiwan or efforts to back Taipei in international organizations or initiatives to strengthen bilateral economic ties. The lesson is that the United States has more room to concretely support Taiwan when it focuses on substance rather than publicly undercutting Beijing’s core domestic narrative that China is making progress toward unification. Chinese authorities will inevitably grumble about quieter efforts, such as expanding defense dialogues between the United States and Taiwan, but these remain below the threshold of public embarrassment for Beijing.

Accordingly, U.S. actions should both meaningfully support Taiwan and give Xi domestic space to proclaim that a path remains open to eventual unification. Examples of such efforts include deepening coordination between the United States and Taiwan on supply chain resilience, diversifying Taiwan’s trade through negotiation of a bilateral trade agreement, strengthening public health coordination, making more asymmetric defensive weapons available to Taiwan, and pooling resources to accelerate innovations on emerging technologies such as quantum computing and artificial intelligence applications. All such efforts would strengthen Taiwan’s capacity to provide for the health, safety, and prosperity of its people without publicly challenging Beijing’s narrative of eventual unification.

In addition, the United States must back its policy with a credible military posture in the Indo-Pacific, placing greater emphasis on small, dispersed weapons systems in the region and making larger investments in long-range antisurface and antiship missile systems. Such investments could bolster the United States’ ability to deny China opportunities to secure quick military gains on Taiwan. And if the United States sends weapons in a low-key manner, it will frustrate Beijing but leave little room for China to justify the use of force as an appropriate response. In other words, the United States should do more and say less.

The United States should also resist viewing the Taiwan problem as a contest between authoritarianism and democracy, as some officials in Taipei have urged. Such a framework is understandable, especially in the wake of Russia’s disastrous invasion of Ukraine. It is easier to convince Americans of the value of a safe and prosperous Taiwan when contrasting its liberal democratic identity with Beijing’s deepening autocratic slide. Yet this approach misdiagnoses the problem. The growing challenge to maintaining peace in the Taiwan Strait stems not from the nature of China’s political system—which has always been deeply illiberal and unapologetically Leninist—but from its increasing ability to project power, combined with the consolidation of power around Xi.

Also Read: Bihar NDA alliance broke due to Sanjay Jaiswal, Vijay Sinha: JDU Minister

Keep watching our YouTube Channel ‘DNP INDIA’. Also, please subscribe and follow us on FACEBOOK, INSTAGRAM, and TWITTER